he Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing Partnership’s latest mixed-income development on Freedom Drive illustrates what it takes to build affordable housing today in Charlotte.

The city’s Housing Trust Fund is contributing $4.5 million to the 185-unit project. Covenant Presbyterian Church is investing $2 million. Charlotte real estate firm Marsh Properties donated 8.1 acres of land. The Movement Foundation, the nonprofit arm of Movement Mortgage, contributed an additional 4.9 acres through a long-term ground lease. The housing partnership received low-income housing tax credits purchased by RBC Tax Credit Equity Group, which generated nearly $7.2 million in equity. BB&T and Bank OZK were also fund investors. Permanent financing was provided by Barings Multifamily Capital and construction financing by Bank OZK.

Despite a long, complicated string of lending and equity sources that totaled tens of millions of dollars, the project barely made it to closing and groundbreaking on Tuesday afternoon.

“We deferred half of our developer fee,” said Julie Porter, president of The Housing Partnership. “We lent money to the deal in order to make it close.”

The Housing Partnership’s situation is not a unique one in Charlotte, a city where housing affordability has become a crippling problem and, subsequently, a major focus for City Council. With construction and land costs skyrocketing, financing a development with any number of below-market-rate units is challenging, to put it mildly. Without government or other subsidy, it is essentially impossible, developers say.

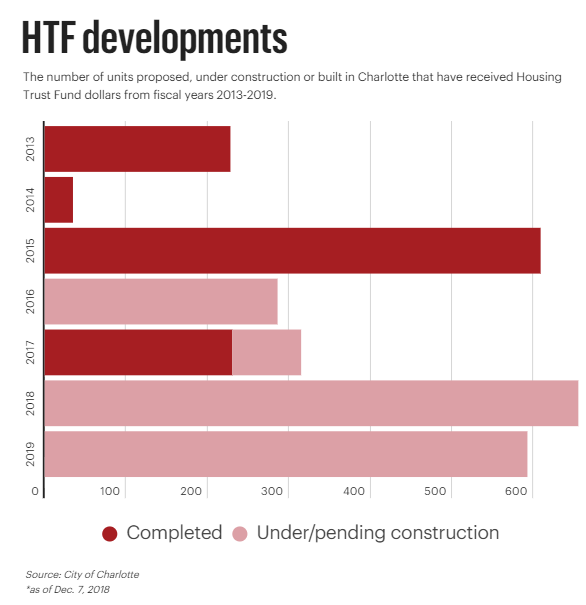

That’s why residential developers who build affordable units as part of their mix hope the city’s bolstered Housing Trust Fund, approved to increase from $15 million to $50 million following last month’s vote, as well as the amount raised by the private sector in the Foundation For The Carolinas’ $50 million Housing Opportunity Investment Fund, will provide much-sought-after gap financing to make a greater number of affordable housing deals work.